Rwanda's government now uses the annual genocide remembrance as a political tool

Over the next 100 days, the government will actively remind citizens of the ethnic divisions that left hundreds of thousands dead

Each year on April 7, Rwanda begins Kwibuka — a 100-day remembrance period for the hundreds of thousands of Tutsis and moderate Hutus killed by Hutu extremists. My research suggests Rwanda's official commitment to Ndi Umunyarwanda disappears during Kwibuka. Instead, ethnic divisions reignite in the public space, professedly in pursuit of reconciliation and unity.

Laws against "genocide ideology" and "sectarianism" ostensibly aid the eradication of ethnic identity and divisions, but they are broad enough to enable human rights abuses and quashing of political dissent. During Kwibuka, the Tutsi-majority government selectively relaxes its position on ethnicity. The government, media and ordinary citizens speak about Tutsi identity but avoid mentioning Hutus, obscuring the name with terms like "perpetrators." Minority Indigenous Twa identity is largely erased.

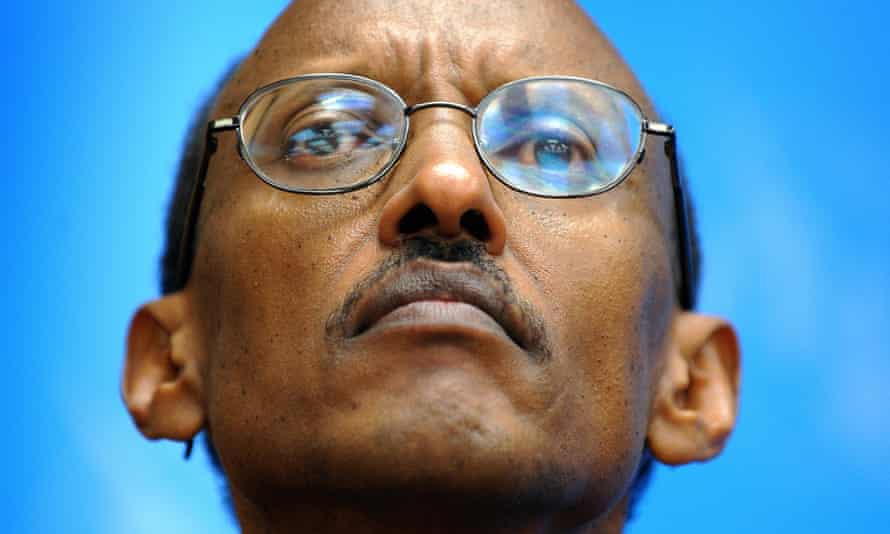

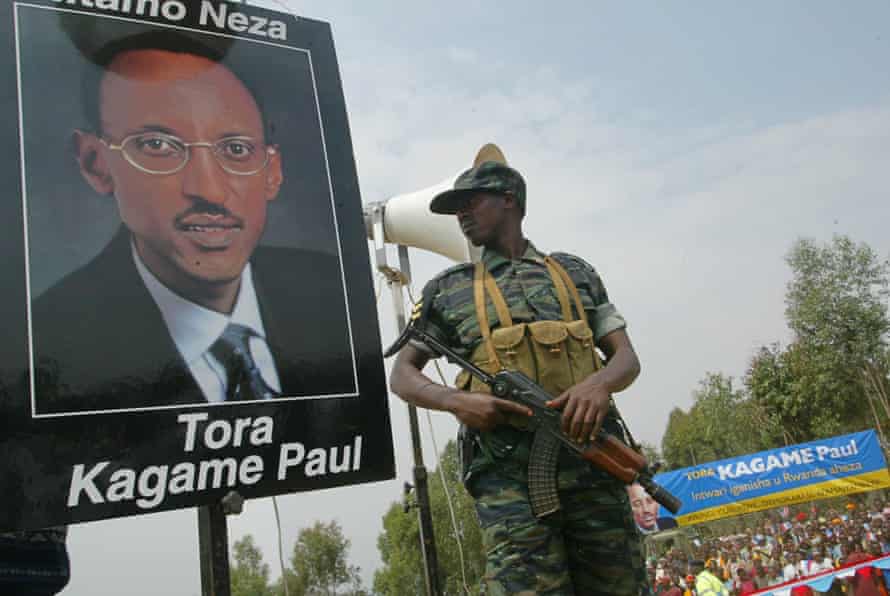

For Kagame, allowing ethnic distinctions to be discussed during Kwibuka helps shore up his reputation as a Tutsi savior, while reinforcing his authoritarian hold and obscuring his own troops' war crimes. In research from 2010-2017, I observed four ways Kagame's government uses ethnic identity and genocide memory in national politics.

Kwibuka reinvigorates ethnic divisions

For all 100 days of this annual period of commemoration, ethnicity is highly visible, contradicting the official policy of ethnic nonrecognition. Kwibuka begins with a week of genocide commemoration events at the local level and within the Rwandan community abroad. Everyone in Rwanda must participate: Businesses and schools close, and citizens report perceiving government authorities step up surveillance to ensure compliance.

Beyond the first week, countrywide radio and television broadcasts are focused on Kwibuka, and community-level commemoration events continue until early July. In all of these activities, ethnicity is central to and explicit in testimonies, skits and speeches — but these activities mention Tutsi as victims and survivors, often ignoring the once-included "moderate Hutus" who were also killed in the genocide.

The government, along with businesses and private citizens, also post state-regulated commemoration signage. During this period, it's not illegal to identify ethnic groups. This signage frequently includes the word "Tutsi" due to the official renaming of the genocide to "The 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi."

Rwandans I interviewed used the terms "Tutsi" and "survivors" interchangeably. Contrary to the reconciliation narrative, many told me Kwibuka is for survivors (Tutsi) only, and noted that anyone who did not attend commemoration events is a type of perpetrator disrespecting Kwibuka.

Rwandans perceive an increase in violence toward survivors

My interviewees confirmed a perceived increase in violence toward genocide survivors during Kwibuka. Every Tutsi interviewee expressed feeling more unsafe than at any other point in the year. Government data show both accusations and convictions of genocide denial and ideology increasing during Kwibuka.

Incidents that lead to accusations and convictions vary widely, from acts of physical violence to disrespect of memorial spaces to benign actions such as a person expressing they do not want to attend memorial events. In 2019, Xinhua reported 69 arrests in the first week alone. While the data could indicate an actual crime spike, the law itself is highly subjective and an accusation is often enough for police to make an arrest and courts to convict.

The government reports more confessions from those imprisoned for genocide crimes

One of the more puzzling aspects of Kwibuka is an inexplicable increase in confessions of genocide-era crimes by incarcerated génocidaires (people who committed genocide). These confessions often lead to the discovery of bodies buried during the civil war. A Rwandan parliamentarian told me government incentives for génocidaire confessions ended years ago; now, "the spirit of Kwibuka" moves the hearts of the imprisoned to confess.

While little is known regarding the actual timing of these confessions, how bodies are identified or who makes the decision to include "found families" in commemoration activities, rights organizations show torture has been used in Rwanda to compel genocide confessions.

These confessions play a very public role. Kwibuka speakers often invoke the mass graves to highlight Kagame's troops as liberators protecting the population from further destruction at the hands of now-exiled genocidaires. Uncovering graves also often requires demolishing homes or businesses. Many self-identified survivors told me bodies were only found on "perpetrator" land and whatever devastation the demolition causes is deserved. Interviewees expressed anger at anyone living on graves, even in cases when the owners moved in long after the civil war and therefore were probably uninvolved in the killings.

Commemoration activities create a Tutsi/survivor identity among younger Rwandans

People too young to have experienced the genocide directly take on genocide survivor and Tutsi identity during commemoration, despite growing up in an ostensibly post-ethnic society. University-age members of "survivor organizations" — which began as "artificial families" for Tutsi youths who lost their biological relatives during the genocide — told me Kwibuka participation was a duty. They organized commemoration events, volunteered as state-trained trauma counselors at those events and enthusiastically supported Kagame's reelection campaign. While all those I interviewed emphasized the universal, welcoming nature of the survivor organizations, only one said he knew a non-Tutsi in his organization.

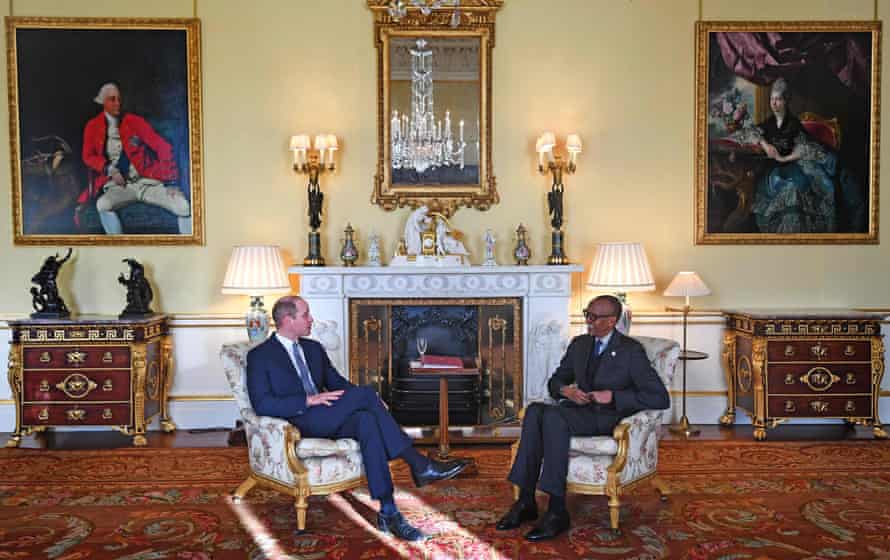

For the other 265 days of the year, Rwanda presents itself as a uniquely post-ethnic nation, but during Kwibuka the ethnic divisions return and become politicized. This year, Kwibuka takes place following the alleged assassination of Seif Bamporiki and the ongoing trial of Paul Rusesabagina, both public critics of Kagame, whose international image may be slipping. Journalists and researchers alike are challenging the one-dimensional progressive savior narrative Kagame has long relied on.

My research suggests the Kwibuka period reaffirms selective official memory of the genocide, and forms a key part of Kagame's case for remaining in power. Long term, the divisions laid bare in the commemoration period point to increasing divisions in Rwanda, rather than reconciliation.

Gretchen Baldwin (@gretchenbaldwin) is a senior policy analyst for the International Peace Institute's Women, Peace and Security program.